Pipeline Fight Sparks Tribal Push for Solar, Wind

By Miranda Willson, E&E News reporter

Sioux tribes in North and South Dakota, galvanized by their experience fighting the Dakota Access pipeline, are now developing solar and wind resources across vast swaths of tribal land to generate revenue and reclaim their independence.

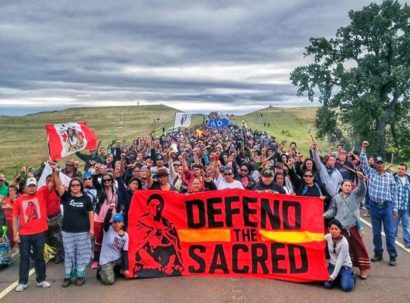

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe drew a national spotlight four years ago after waging a fight against the construction of the $3.8 billion oil pipeline, a project the tribe cast as an intrusion on its land and a threat to water supplies and cultural resources.

Now tribal leaders are planning to build a 235-megawatt wind farm through a newly created public power authority as a means to create jobs, generate revenue and develop a homegrown source of carbon-free power.

“We want to control our own destiny,” said Joseph McNeil Jr., general manager of SAGE Development Authority, the tribe’s new public power authority. “That’s been the bottom line for a long time, and particularly when DAPL hit — that we earn, build and maintain our own power supply.”

Slated to come online in 2023, SAGE’s wind farm will bring money and jobs to the Standing Rock reservation, McNeil said. The project has financial backing from the Sierra Club Foundation, the Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors and others, although the Standing Rock Sioux is also seeking donations from a crowdsourcing campaign, McNeil said.

In parallel, a coalition of six Sioux tribes — including the Standing Rock Sioux — have formed the Oceti Sakowin Power Authority (OSPA) and have plans to build a 2-gigawatt network of wind turbines in the Dakotas. Apex Clean Energy is developing OSPA’s first two planned wind installations: the 120 MW Pass Creek wind project on the Pine Ridge Reservation and the 450 MW Ta’teh Topah wind farm on the Cheyenne River Reservation, said Caroline Herron, project manager of OSPA.

These efforts mark a shift for Native Americans, who have historically played a reactive role in energy development, said Nicole Ducheneaux, partner at the law firm Big Fire Law and Policy Group.

“We’ve spent a long time in the last 400 years reacting to various intrusions into our lands,” said Ducheneaux, a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. “Now our members have gone to college, become educated, become engineers and lawyers, and we don’t have to be reactive anymore. We can participate in the economy and industry in a way that’s proactive.”

The Standing Rock Sioux’s proposed wind farm would complement an existing 300-kilowatt solar farm on the reservation, the largest solar installation in North Dakota. Located in Cannon Ball about 3 miles from the DAPL crossing, the solar farm powers a youth activities center and a veterans’ building, said Cody Two Bears, a former Standing Rock Sioux tribal council member who spearheaded that project.

Since the solar array came online in 2018, it has offset Cannon Ball’s collective electricity costs by about $10,000 per year, which is critical for a community where nearly half the population lives below the poverty line, according to Two Bears.

As the tribal council leader at Cannon Ball during the #NoDAPL protests, Two Bears said the movement inspired him and others to rethink the tribe’s reliance on resources extracted at faraway locations. He was also interested in creating a project exemplifying the tribe’s desire to protect the environment.

“If Standing Rock can bring people all over the world talking about climate change and water and protecting our water and the environment, then we better do something about it,” he said.

OSPA tribal members — the Cheyenne River, Flandreau Santee, Oglala, Rosebud, Yankton and Standing Rock — were also energized by the #NoDAPL movement, Herron said. Some of the tribes have been fighting the Keystone XL pipeline or other energy projects as well, she said.

“All of those things have definitely influenced the tribes we work with and are part of why the renewable energy mandate is so powerful for them,” she said.

Overcoming obstacles

Tribes have historically faced challenges in building utility-scale renewable energy. Some proposals have been clouded by concerns about whether the benefits would reach tribal communities or simply enrich developers, said Faith Spotted Eagle, chair of the Yankton Sioux’s treaty committee and an adviser to OSPA.

“People would say, ‘Why are we going to hire them if they’ll get the profits and we’ll only get a little bit?'” Spotted Eagle said.

According to a 2016 report from the Department of Energy that surveyed 24 tribal energy experts, securing financing and funding is the most common roadblock tribes experience in developing renewable energy. Persistent underfunding of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and complex bureaucratic processes are part of the problem, Herron said.

“[The BIA] has specific rules, and the rules weren’t always created for these leases based on a good working knowledge of how a project would be developed,” she said.

Utility-scale projects also often cross federal and tribal land as well as other jurisdictions, complicating the approval process. In the case of the Yankton Sioux Reservation in South Dakota, the federal government over the years allotted acres to the tribe in pieces, resulting in a “checkerboard” pattern of native and non-native land ownership throughout the reservation, Spotted Eagle said.

In addition, tribes located in remote locations might have trouble finding prospective buyers for renewable energy, said Elizabeth Kronk Warner, dean of the University of Utah’s S.J. Quinney College of Law and a tribal law expert.

“A lot of tribes are in locations that would make them prime developers of wind energy, but the transmission capacity isn’t there and there isn’t the large population center to benefit from that energy around them,” Warner said.

Nonetheless, OSPA is making progress on its first two wind farms, which are expected to come online in 2024. The public power authority is in talks with potential purchasers for the electricity the wind farms will generate, Herron said.

“The benefits and opportunities such projects will bring to these impoverished and underserved tribal communities in jobs, training, needed infrastructure and other investments has really resonated with potential buyers,” Herron said in an email.

The Sioux tribes hope their efforts could provide a template for other tribes looking to capitalize on their renewable energy resources. In teaming up with foundations, SAGE has forged a new funding path for these types of projects, McNeil said.

The tribes want to show that foundations are “always looking for ways to do good for these communities,” he said.

To Ducheneaux, the Sioux tribes’ renewable energy initiatives reflect the resilience and resourcefulness of Native American tribes, many of which are located on prime lands for solar and wind energy.

“When they were dispossessing us of land, they were like, ‘Great, we’re going to give them this barren windy prairie,'” Ducheneaux said. “But that barren windy prairie, in the case of Standing Rock, now has the ability to generate beautiful clean energy in the form of wind. That’s part of the paradigm shift.”

You Might Also Like

On July 6, 2020, The New York Times reported on the ruling of a district court that the Dakota Access Pipeline must shut down pending an environmental review and be emptied of oil by August 5, marking a huge victory for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and other Native American and environmental groups who have […]

On August 25, The Bismarck Tribune published an article about SAGE Development Authority’s plan to develop the Anpetu Wi Wind Farm at Standing Rock and the crowdfunding efforts that will help bring this plan to fruition. “About 60 turbines are slated to dot the Porcupine Hills, a badlands-esque part of Sioux County between Fort Yates […]